THE PORT - MANUFACTURING (1960)

Who knows for how long port and city have influenced each other and evolved together: the growth of one leads to the development of the other and again this encourages new structures and new economies in the human community.

1964: under construction - the conveyor belt from the Steelworks Hub to the port (from Simonetti M., 'The port of Taranto - port of industrial development in southern Italy', Rome 1966)

The inauguration of the Shell terminal in 1967

THE CONTEMPORARY WORLD

While the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869 seemed to offer new opportunities for Italy and the Ionian Sea, which opened up to intercontinental traffic, it would be the post second-world-war period that changed the commercial and industrial strategies of southern Italy.

A major engineering feat, completed in 10 years of continuous work, the Suez Canal opened to maritime traffic in 1869. 161 kilometres long, it links the Mediterranean with the Red Sea, allowing ships to reach the Indian Ocean without having to circumnavigate Africa.

Further information

The impact on the transport system of the time was disruptive. The routes from Europe to India and the Far East were almost cut in half, allowing, for example, a ship bound from London to Calcutta to reduce its voyage by about 10,000 km, so shifting commercial strategies and political balances. At the beginning of the 20th century, port traffic benefited from Taranto’s inclusion on the London-Bombay shipping route and the commercial route from Genoa to Venice, with one steamer arriving and one departing every week. This also contributed to port traffic.

The Post WWII-period and Industrialisation

During the 1960s the industrial developments were located in the immediate vicinity of the port, which thus acquired a typically industrial appearance and function. Commercial and military operations remained. From 1963, the year in which some of the units of the IV Centro steelworks entered operation, the industrial port became one of the top-ranking in Italy for quantity of cargo handled.

The city, port and surrounding area evolved together. In addition to the cement factory, the food industry also added to the port traffic with its products: beer, oil, wine and baked goods.

Saint Catald, protector of sailors

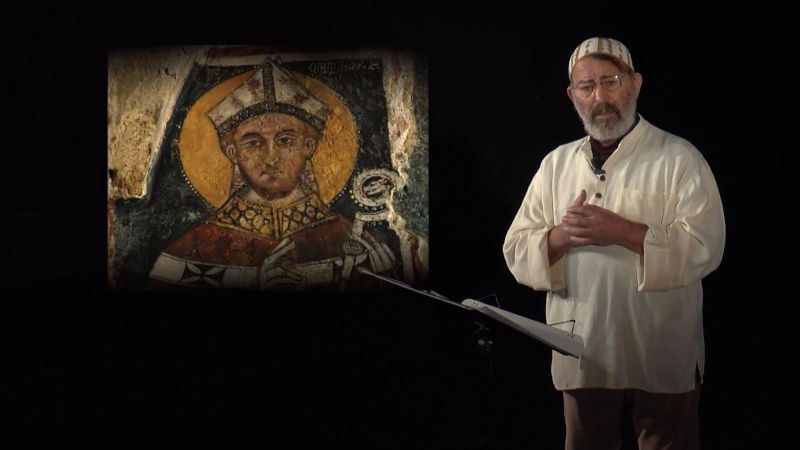

Video with Recording by Giovanni Guarino

Giovanni Guarino, actor and storyteller from Taranto, tells the story of the city's patron saint, the Irish monk Catald, who, in the 7th century, stopped in Taranto on his way back from the Holy Land and became its bishop, patron saint and... protector of sailors.

frontispiece of a life of St. Catald from 1727 (from Google Books)

THE MODERN PERIOD

From the Austrians to the Bourbons, a revival of the commercial port

A 1717 chronicle by the Taranto priest Cataldo Antonio Cassinelli records that the port was frequented not only by Venetian ships, but also by ships coming ‘from distant lands of England, Holland, Spain and Portugal‘, which ‘sail there daily, loading up with wheat, grain, wine, wool, oil, cheese and shellfish, or bringing new merchandise to sell’.

There are, among the products exported to the ‘Kingdom of Naples, and other more distant countries; the oysters by the end and black Tarentine mussels are without number; so that there was one who in this regard compared them to the stars of Heaven’.

the first Bourbon period, in the middle of the eighteenth century

Oil remained one of the most traded products from the Apulian ports. Taranto continued to satisfy the demand from England and a new trade route to France was established. In addition to oil, other traditional products from Apulia, such as wheat and wool, were sent by ship.

In 1755, work began on reopening the canal ditch, which tended to silt up, isolating the Mar Piccolo and its farms from the open sea.

At the end of the eighteenth century we know that products from Lucania and Calabria (dried figs) were also arriving by haulage boats in the short natural bend to the north-west, which was relatively sheltered but lacked quays and harbour facilities.

French Taranto

The Napoleonic period confirmed more decisively the Mediterranean role of the port of Taranto, a role that would become more specific with the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869. New traffic, new balances and new disputes affected the port in this period while, with the unification of the Kingdom of Italy, firstly the naval and coastal defence necessities were identified, then the expansionist, colonial and political ones, directed towards the Mediterranean, the Balkans and Africa.

The vision of the Napoleonic state

Napoleon asked General Soult and Admiral Villeneuve to study the port of Taranto and stipulate the works necessary to give it maximum efficiency and security. The works, carried out in a very short time, concerned the wide harbour, which was fortified at its entry points; the island of S. Paolo on which batteries were installed and the fortification of Capo di S. Vito. On the island of S. Nicolicchio, which overlooked the Rondinella pass and the anchorage of the merchant port, another battery with several cannons was placed.

And thus, with the decree of 3 September 1813, the port of Taranto was declared a military port and therefore under the authority of the Ministry of War and the Navy.

The Continental Blockade

The French occupation of Apulia was not tolerated by the English government. In response, Napoleon set up the so-called ‘continental blockade’ to prevent England from trading with the ‘continent’ (Western and Central Europe), but this embargo had repercussions on the fragile economy of Salento, which at that time was based mainly on the sale of oil and wine abroad, above all to the Low Countries and England.

The wind of modernity

On the whole, Taranto benefited from the French reorganisation, as can be seen from the increase in population: in 1814, the city had more than 14,000 inhabitants. With the 'feudal eversion' law of 1806, noble and ecclesiastical privileges were abolished.

Along with other ancient impositions, in 1806 the rights over the Taranto fishing boats were abolished, so the number of fishermen and sailors increased (748 out of the 1,202 in the Territory of Otranto). By then, the black mussels produced in Taranto were traded throughout the province and even outside, in neighbouring regions, with a gross income of 40,000 ducats, to which was added the income from fishing for other seafood and fish of all kinds

The salting of fish, although a long-standing tradition, was underdeveloped at this time.

from the unification of Italy to initial industrialization

The merchant port, once so flourishing and a hive of activity, had fallen into a real crisis during the last period of Bourbon rule. It was only with the unification of the Kingdom of Italy that it was thought to enlarge it and make it suitable for receiving even the large steamers, ships powered by steam that were starting to ply the Mediterranean and oceanic routes.

The decision to install a naval base there led to the need to also construct the Military Arsenal. It was really this large shipyard that altered the appearance of the city and the port, which saw its traffic increase considerably, especially during the First World War.

EUROPE OF THE GREAT MONARCHIES AND ITALY OF THE PRINCIPALITIES (TITLE)

The commercial revival with King Ferdinand of Aragon

After the death of Prince Orsini del Balzo, Taranto seemed to be embarking on a period of economic recovery, shown by the reactivation of the local agricultural, fishing and marine industries.

The presence of foreign merchants (above all Venetians) gave new impetus to commercial trade.

A new Fair by decree of King Ferdinand of Aragon

In 1463, when Ferdinand of Aragon incorporated the principality into the kingdom’s domain, the people of Taranto, remembering the misery and excesses to which they had been subjected under Prince Orsini del Balzo, asked for concessions to revive the city’s economy.

King Ferdinand first of all established a new fair, in addition to the two held ‘annually, free of all duties, in the square near the customs house, dedicated to St Anthony the Abbot, in the month of January from the feast day of the saint for the next seventeen days’. (from PORSIA F. and SCIONTI M., “Cities in the history of Italy – Taranto, Laterza, Rome-Bari, 1989).

The privilege of not having to ``arm galleys``

King Ferdinand renewed a privilege already granted to the city by King Ladislaus of Naples in 1407, according to which the people of Taranto were exempt from the obligation, common to maritime cities, of arming galleys [providing equipment and crew] for the royal fleet. It also regulated the sale of fish, which was already subject to special rules at the time of the principality.

``Foreign`` Merchants in the Fifteenth Century

The Account of the Treasurer of Taranto gives us a list of names of foreign merchants who “infondacano” (deposited their goods in warehouses) in the port of Taranto: there were 9 Venetian merchants, 1 Veronese, 1 Milanese, 1 Bergamasque, 2 Ragusans (from Ragusa, now Dubrovnik, in Croatia). Among the goods present were: iron, wood, linen, velvet, silk, Bulgarian hides, cheese and pepper.

New water and defensive works

After the War of Otranto (1480-81), in the autumn of 1481 a first navigation canal was built, narrower than the present one and with irregular banks, to allow the passage of small boats and better defend the castle, which was not then what we see today.

We can still see the Roman ditch, which was blocked by debris and could no longer be used by large ships.

Improvements to the harbour basin enabled the people of Taranto to participate in the armament of the royal fleet commissioned by King Ferrante. However, work on the fortifications came to a halt: a tax on fishing was proposed to compensate for the lack of funds.

Aragonese shipyards

In 1489, the people of Taranto obtained special concessions on the payment of taxes on iron, pitch and timber, the so-called ‘terzarìa’, which required them to pay one third of the value of the raw material to the royal customs. Thus, the Taranto shipyards were able to build ‘three beautiful ships of about three hundred butte’ each.

Butte stands for botti (‘casks’, one ‘cask’ = 12 ‘barrels’ = c.523l), the unit used in the 15th century to measure the capacity of a ship. Three hundred botti corresponded to about 84 tonnes of cargo

At that time, there were also galleys capable of carrying 250 tonnes, but the preference was for smaller merchant ships that travelled in flotillas (muda). The three ‘beautiful ships’ mentioned above probably formed a ‘muda’.

The Spanish period (1503-1707)

In the first decades of the 16th century, the Spanish Viceroys did not invest in the ports of Puglia. But towards the end of the 1650s, their goal became to fortify and close the ports against continual assaults by pirates; in the meantime, the port structures had become neglected and silted up, losing the predominance they had enjoyed in the Middle Ages.

Florentine merchants operated in Taranto, often employing Ragusan ships, exporting wheat to Genoa and Viareggio, which was mostly used to produce the ‘biscuit’ needed by the fleet or sent to Naples or Spain to provide rations. This trade was supplemented by the export of oil and spun cotton.

The English in Taranto

During the 17th century, the Venetians were replaced by the English, who came to import oil into England. Evidence of this trade is the presence of an English consul in Taranto to support commercial activities, and there was also a vice-consul from Ragusa (present-day Dubrovnik), a city that evidently equipped ships and carried out transportation for third parties.

from the Austrians to the Bourbons

During the Austrian period of the Habsburgs in the early eighteenth century, no attention was paid to the commercial use of ports. The lack of interest in the Apulian ports can also be attributed to the fact that they could have been potential competitors for Trieste, which in those years was taking on the role of Austria’s maritime outlet in the Mediterranean. Nevertheless, somehow the commercial traffic with northern European countries was maintained.

FROM THE NORMANS TO THE RENAISSANCE

Prismatic marble stele (stone slab) with kufic inscription. 12th century AD; found in Taranto, S. Maria del Galeso (photo MArTa)

Robert Guiscard

With the conquest of the Norman Robert Guiscard in 1080, a period of relative tranquillity began for Taranto. From this moment on, the southern port system was regulated.

Merchants and ships’ captains paid numerous state and feudal duties for imports and exports. Payments were made for landing, be it only anchorage or phalangage (i.e. the possibility of planting poles to which to moor or making use of existing ones).

You paid for lanternage, a tax for ports with a lighthouse, and also for fishing. To monitor this there was the Mastro Portolano (Master Portolan) for the Territory of Otranto, who supervised the customs officers of the province, the traffic and obtaining precise data from his officers, the portulanoti.

Robert Guiscard crowned duke by Pope Nicholas II in Melfi, miniature (from Wikimedia, manuscript Nuova Cronica - ms. Chigiano L VIII 296)

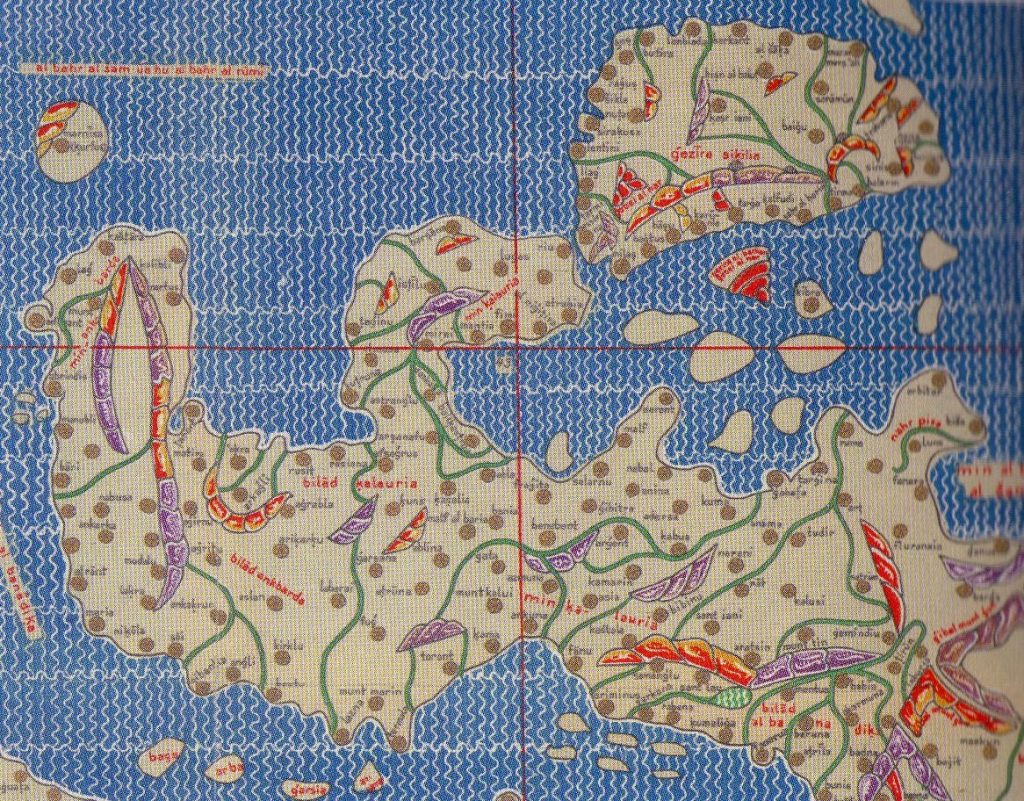

The book of King Roger

In his ‘Book of King Roger’, the Maghrebi geographer and traveller Al-Idrisi (1099-1164) describes Taranto as “a large city, of ancient construction and remote origin, with beautiful buildings and sumptuous palaces. It is frequented by merchants and travellers. There, ships are loaded and caravans arrive, being furnished with an abundance of wares and riches.

The city has a harbour in the open sea from the west and from the east by the north wind it has a small sea that measures twelve miles around, going from the bridge to the city side. This bridge is between the open sea and the small sea; it is three hundred cubits long from the gate of Taranto that looks north to the mainland, and it is fifteen wide”.

The port in Angevin times

We can imagine the working activities at the port of Taranto in the Angevin period from what we would today call the ancillary industries.

We know that in 1284 as many as one thousand five hundred “cannate” (=15,000 kg) of fleet biscuits, i.e. the main food of the sailors on board ship, were produced. This kind of biscuit could last for months or even years without spoiling, thanks to a special blend of unrefined flours whose composition has been lost to this day.

If those 15 quintals of biscuit supplied the crews in transit from the port of Taranto in 1284, one can imagine a wide range of work around the movement of ships, such as the preparation and trading of salted fish.

Giovanni Antonio Orsini del Balzo

From an inventory compiled by Prince Giovanni Antonio Orsini del Balzo around 1435, we know that at that time there were “fishponds” all over the Mar Piccolo and also in the Mar Grande. Taxes were strictly regulated, a tax being paid according to the types of fish caught, the fishing techniques used and the seasonal or daily fishing periods.

Few fishponds were exempt from taxation, and it was established from time immemorial that fishermen in the Mar Piccolo could only fish from sunset until the early night.

The customs house was in what is now Piazza Fontana, but the prince moved it elsewhere to expand the working space in the piazza, which was soon capable of accommodating three galleys undergoing maintenance.

TARANTO IN THE ITALY OF LATE ANTIQUITY

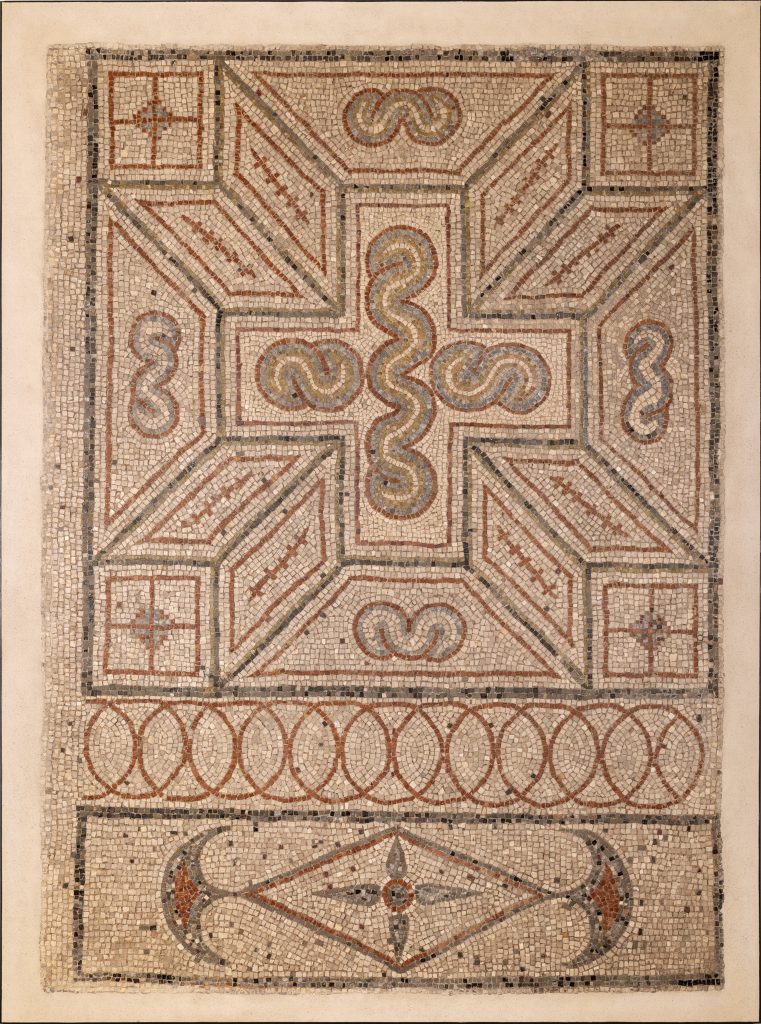

Polychromatic floor mosaic from 5th century A.D. Taranto, found in via Cavallotti, at the corner of via Nitti, in the area adjacent to Casa Basile, 1909. (photo MArTa)

the end of the western roman empire

Taranto was involved in the war between the Ostrogoths and the forces of the Eastern Roman Empire (535-553). The Byzantines, who emerged victorious, built the city's first fortifications.

Subsequently, Emperor Constans II (630-668), aiming to contain the Lombards in Apulia, arrived from Athens and landed in Taranto with a large army, in a fleet made up of dromons [link to Byzantine warships], the Byzantine warships.

The early Middle Ages were marked by the passage of Goths, Lombards and Saracens to Taranto, the latter assaulting it in 927 to deprive the Byzantines of one of the best ports in their domain.

Forty years later, in 967, Taranto was rebuilt by the Byzantine emperor Nicephorus II Phocas (912-969), although the port began to lose its military, strategic and commercial importance in favour of the Adriatic ports of Otranto, Brindisi and, later, Bari.

Byzantine Emperor (963 to 1969) Nicephorus Phocas in a 16th century printed edition ( Giovanni Battista Cavalieri & Thomas Treterus, Romanorum imperatorum effigies, Rome, Vincenzo Accolti, 1583, from Wikimedia Commons)

Coin hoard consisting of 8 solidi (bezants). Vth-VIth century AD. Found in Taranto, via Nitti, at the corner of via Pitagora, from the D'Ayala Valva property, 1915. (Photo Mar-ta)

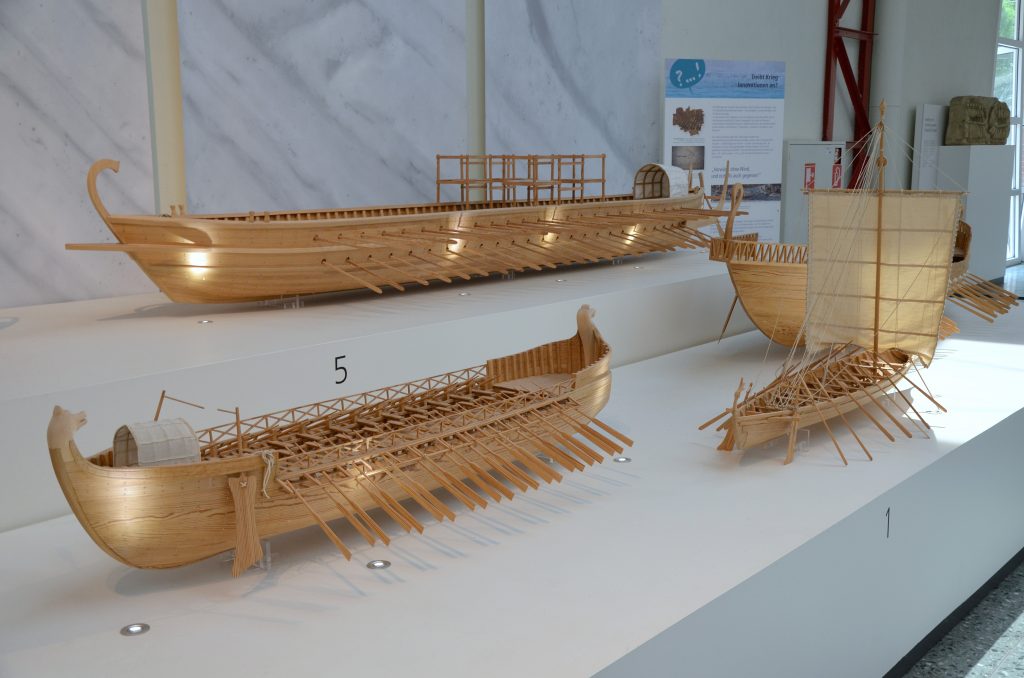

Byzantine warships

In order to securely reconquer Apulia, Constans II set up a powerful fleet of troop carriers, escort ships, cargo ships and finally “steed ships” (horse transports).

The dromon was the warship in use at this time; it was a descendant of the less agile Roman liburna and carried 100 oarsmen, 50 landing troopers and about ten men including the commander, helmsman and others.

The cargo ships, for provisions and troops, were bulkier and could hold a maximum of 300 men. Lastly, the “steed ships” were equipped to transport horses, which entered the ship through a large hatch on the side at the stern. The special arrangements for the transport of horses were such that no more than 100 were permitted.

Model of a Byzantine dromon (10th-12th cent.) (photo by Carole Raddato, Museum für Antike Schiffahrt, Mainz)

TARANTO IN THE ROMAN ERA

The port regained importance under Roman rule.

During this period, the moat was created where the navigation canal is today. Literary sources and archaeological finds make it possible to locate the port basin along the shore of the Mar Piccolo that runs from the moat to the small bay of S. Lucia (today used by the Military Arsenal).

But there was also a quay on the Mar Grande that was served by the Triglio aqueduct, which brought fresh water from the springs north of the city to supply the ships.

In 125 B.C. Taras became a Roman colony, under the name of Neptunia, and the Roman city took the Latin name of Tarentum.

The Triglio aqueduct

It is a feat of engineering that brought water to Taranto from Roman times until the 19th century. The aqueduct is made up of a series of artificial underground tunnels and a surface section dating back to the post-Roman period, supported by arches that cross the municipalities of Crispiano, Statte and Taranto.

The aqueduct, built around the 1st century BC, after the founding of the colony Neptunia on the ruins of Taranto, supplied water to the villas on the outskirts of Taranto and not to its urban centre. The water system reached a quay on the Mar Grande to supply ships.

After the fall of the Roman Empire in 545, water for public use was also brought into the city at the behest of Totila, king of the Ostrogoths,

Restorations and extensions were carried out during the Byzantine period, then in the 14th century with funds from Catherine of Valois, then with the Aragonese (1469, the fountain in the Gran Piazza), and in 1543 (the arches commissioned by Charles V together with the monumental fountain).

Note di approfondimento

The hydraulic system collected water from numerous springs in the Murge Tarantine hills. A dense network of underground tunnels, about 18 km long, poured the spring water into a large rocky cistern located at a depth of 9-10 m; from this, which acted as a collector, the main pipeline departed.

The Triglio aqueduct, 2nd century B.C. - 16th century A.D.,(photo Sergio Malfatti)

A witness from the second century B.C. recounts

The Greek historian Polybius, who lived in the second century B.C., writes in Book 10 of his Histories about the importance of the port of Tarentum:

“The whole of the Italic coast from the strait and the city of Reggio to Tarentum for the length of 2000 stadia and more [over 320km], is completely devoid of ports, with the exception of the port of Tarentum which faces the sea of Sicily and looks towards the regions of Greece.”

Polybius considers Taranto and its surrounding populations

“That stretch of land is densely inhabited by barbarian peoples and boasts the most illustrious Greek cities: in it are found the Bruzi, the Lucani, part of the Dauni, the Calabrians and many other peoples. The Greek cities of Reggio, Locri, Caulonia, Crotone, Metaponto and Turi also occupy this coast. So whoever from Sicily and Greece is going to one of the above-mentioned places necessarily lands in the port of Taranto, and within this city take place all the exchanges and trades with the inhabitants of this region of Italy”.

The frontispiece of Polybius' Histories, Chap. 10, in a printing from 1751, tells of the port of Taranto in the 2nd century BC. (from Google Books)

The Roman port as described by Strabo

Among the ancient literary accounts of the port of Taranto is that of Strabo, who wrote his Geography at the beginning of the 1st century, giving a detailed description of the port area of Taranto. In those days, the precious purple-dyed fabrics [Link to purple] so sought after by Roman aristocrats were shipped from here.

“While most of the gulf of Taranto is devoid of ports, in Taranto there is a very beautiful and wide harbour with a perimeter of 100 stadia [between 15 and 18km], enclosed by a large bridge. An isthmus is formed between the bottom of the harbour and the open sea, so that the city stands on a peninsula, and since the neck of the isthmus is not very high, ships can easily be hauled from one side to the other.”

Figure of a dancer in polychromatic terracotta from 225-175 BC, found in Taranto, via G. Giovine, at the corner of via Marche, 1951. (photo MArTa)

reconstruction of the Roman liburna at the port of Civitavecchia, created by Matteo Collina (from the website Civitavecchia.Portmobility.it)

FROM ANTIQUITY TO THE MAGNA-GREEK PERIOD

The first landing: the ``Tuna Rock``

In 1899, the excavation of the Scoglio del Tonno (“Tuna Rock”), a promontory to the west of the mouth of Mar Piccolo, during the construction of the mercantile harbour quay, brought to light the remains of a Bronze-Iron Age settlement. An active and growing community had already been identified in the area over a period of time stretching from the Middle Neolithic to the 12th century BC: they had found ‘cave tombs’ and noted the use of red ochre in funerary rites.

And then the presence of Lipari obsidian (a volcanic glass much sought after and traded in antiquity to make weapons and sharp implements), and a deposit of ceramics from the Mycenaean period (14th-13th centuries BC) suggests the presence of an actual settlement there already at that time.

The port today from above, with the city in the background

Bronze pin with a double spiral head decorated with engraving. 1300-1000 BC, found in Taranto, Scoglio del Tonno, 1899. (photo MArTa)

From antiquity to the present day

The port of Taranto has been of significance in different historical periods from a commercial point of view. Beginning with the Magna-Greek period and continuing until the mid-eighteenth century under Bourbon rule. In the French decade, at the beginning of the 19th century, it established itself as a military stronghold, and the same was true after the Unification of Italy.

Neolithic pottery

Further information

- From a flourishing town in Magna Graecia to a Roman colony, from the decline during the Saracen and barbarian invasions to recovery under the Normans. After the Angevins and the heavy taxation of Prince Orsini del Balzo, the resumption of commercial trade under the Aragonese revived the city, a prosperity that returned in the 18th century under the Bourbons.At the beginning of the 19th century, Napoleon Bonaparte began to consider the port mainly as a military stronghold..

- With the unification of Italy, the military role of the port was reaffirmed, but the commercial aspect also benefited, thanks to the construction of the New Arsenal, which marked the first phase of the city’s industrialisation; this was followed by a second phase in the 20th century, during the years of the economic boom, when the appearance of the port and the city changed: the industrial sites adjacent to the port basin gave the port a typically industrial appearance, and in terms of volume of shipments it rose to be among the top-ranked locations nationally.The port tried to keep up with the development of the industries based in Taranto.

Map of Southern Italy

foundation: myth and archaeological evidence

Historical tradition dates the foundation of Taranto to 706 BC, by a Spartan warrior, Phalanthos, who landed on the shores of Taranto. The archaeological findings at the Scoglio del Tonno (“Tuna Rock”) [link to Scoglio del Tonno] (near the present stone bridge) confirm commercial contacts between the Greeks and the indigenous peoples.

The port of Taranto, during the city’s period of greatest splendour, from the 6th century BC until the Roman conquest, was the busiest of the southern ports. The power of its fleet and commercial activities gave ancient Taras considerable political and economic influence, as can be seen from the wide distribution of Tarantine coins [Link to coins minted in Taranto] and ceramics.

Transportation amphora 'Corinthia B', Corcyraean, from the 3rd century BC found in Taranto, via Dante, at the corner of via Polibio, Rione Italia, 1958. (photo MArTa)

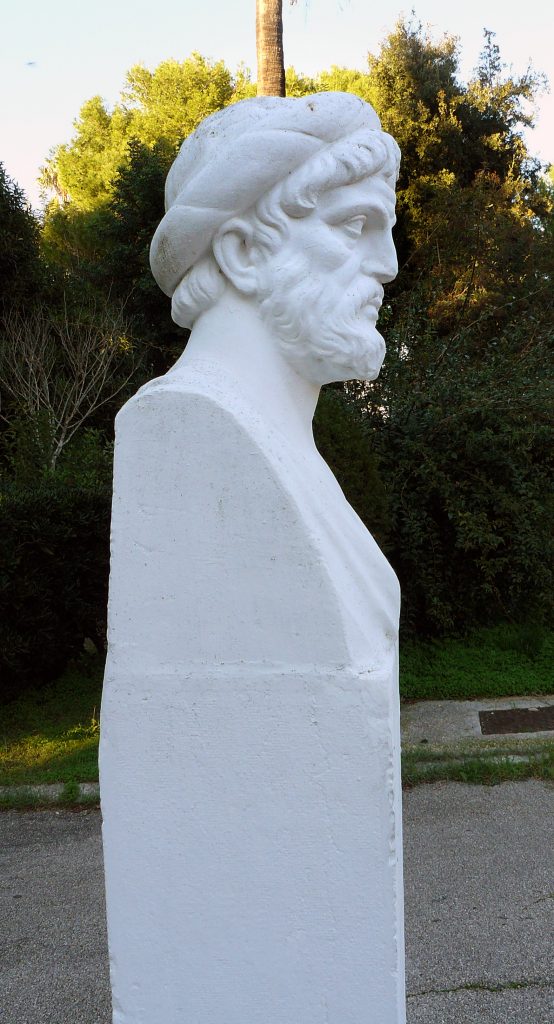

the figure of Archytas

After the mythical Phalanthos, who is said to have founded the city following the words of the oracle of Delphi, it was Archytas (428-360 B.C.) who brought Taranto to its greatest splendour. Elected seven times as ‘stratego’, i.e. military commander and governor of the city, he implemented a development policy that led Taranto to become the richest and most important metropolis of Magna Graecia. By building temples and monuments he gave the city a new appearance; he encouraged trade by sea, strengthening relations with various coastal cities in Sicily, Istria, Greece, North Africa and Asia Minor.

The sea was in his destiny: he died in a shipwreck near the promontory of Mattinata, in the Gargano, during an action supporting the Syracusans in the Adriatic area.

the bust of Archytas at Villa Peripato (photo Salvatore Tomai)

Archytas in the sciences

Archytas was an eclectic man: a Pythagorean philosopher, he was also a friend of his contemporary Plato (428-348 BC); as a mathematician he described the properties of the cube; as a mechanical engineer he built a flying machine known as Archytas’ Dove; as a musician, he adjusted the spacing of the flute’s holes in order to achieve better harmony, and invented a machine for making various sounds.

The poet Horace (65-8 BC) composed an ode in his honour, describing him as

“measurer of the sea, and of the earth, and of the numberless sands; and a man who on the celestial spheres dared to rise and wander”.

the bust of Archytas at Villa Peripato (photo Salvatore Tomai)