GRANDI MONARCHIE ENG

EUROPE OF THE GREAT MONARCHIES AND ITALY OF THE PRINCIPALITIES

THE COMMERCIAL REVIVAL WITH KING FERDINAND OF ARAGON

After the death of Prince Orsini del Balzo, Taranto seemed to be embarking on a period of economic recovery, shown by the reactivation of the local agricultural, fishing and marine industries.

The presence of foreign merchants (above all Venetians) gave new impetus to commercial trade.

A NEW FAIR BY DECREE OF KING FERDINAND OF ARAGON

In 1463, when Ferdinand of Aragon incorporated the principality into the kingdom’s domain, the people of Taranto, remembering the misery and excesses to which they had been subjected under Prince Orsini del Balzo, asked for concessions to revive the city’s economy.

King Ferdinand first of all established a new fair, in addition to the two held ‘annually, free of all duties, in the square near the customs house, dedicated to St Anthony the Abbot, in the month of January from the feast day of the saint for the next seventeen days’. (from PORSIA F. and SCIONTI M., “Cities in the history of Italy – Taranto, Laterza, Rome-Bari, 1989).

THE PRIVILEGE OF NOT HAVING TO `ARM GALLEYS`

King Ferdinand renewed a privilege already granted to the city by King Ladislaus of Naples in 1407, according to which the people of Taranto were exempt from the obligation, common to maritime cities, of arming galleys [providing equipment and crew] for the royal fleet. It also regulated the sale of fish, which was already subject to special rules at the time of the principality.

`FOREIGN` MERCHANTS IN THE FIFTEENTH CENTURY

The Account of the Treasurer of Taranto gives us a list of names of foreign merchants who “infondacano” (deposited their goods in warehouses) in the port of Taranto: there were 9 Venetian merchants, 1 Veronese, 1 Milanese, 1 Bergamasque, 2 Ragusans (from Ragusa, now Dubrovnik, in Croatia). Among the goods present were: iron, wood, linen, velvet, silk, Bulgarian hides, cheese and pepper.

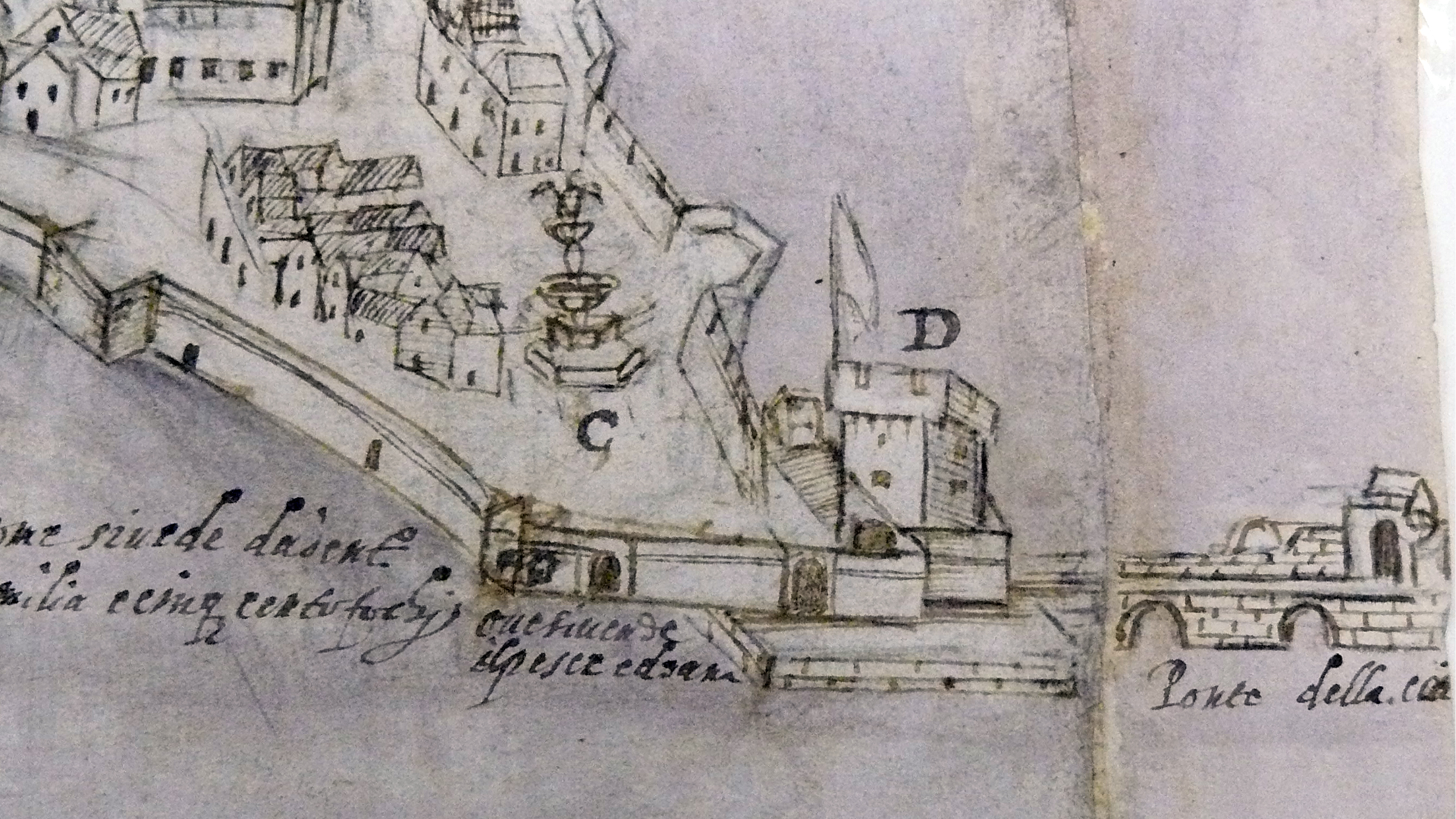

NEW WATER AND DEFENSIVE WORKS

After the War of Otranto (1480-81), in the autumn of 1481 a first navigation canal was built, narrower than the present one and with irregular banks, to allow the passage of small boats and better defend the castle, which was not then what we see today.

We can still see the Roman ditch, which was blocked by debris and could no longer be used by large ships.

Improvements to the harbour basin enabled the people of Taranto to participate in the armament of the royal fleet commissioned by King Ferrante. However, work on the fortifications came to a halt: a tax on fishing was proposed to compensate for the lack of funds.

ARAGONESE SHIPYARDS

In 1489, the people of Taranto obtained special concessions on the payment of taxes on iron, pitch and timber, the so-called ‘terzarìa’, which required them to pay one third of the value of the raw material to the royal customs. Thus, the Taranto shipyards were able to build ‘three beautiful ships of about three hundred butte’ each.

Butte stands for botti (‘casks’, one ‘cask’ = 12 ‘barrels’ = c.523l), the unit used in the 15th century to measure the capacity of a ship. Three hundred botti corresponded to about 84 tonnes of cargo.

At that time, there were also galleys capable of carrying 250 tonnes, but the preference was for smaller merchant ships that travelled in flotillas (muda). The three ‘beautiful ships’ mentioned above probably formed a ‘muda’.

THE SPANISH PERIOD (1503-1707)

In the first decades of the 16th century, the Spanish Viceroys did not invest in the ports of Puglia. But towards the end of the 1650s, their goal became to fortify and close the ports against continual assaults by pirates; in the meantime, the port structures had become neglected and silted up, losing the predominance they had enjoyed in the Middle Ages.

Florentine merchants operated in Taranto, often employing Ragusan ships, exporting wheat to Genoa and Viareggio, which was mostly used to produce the ‘biscuit’ needed by the fleet or sent to Naples or Spain to provide rations. This trade was supplemented by the export of oil and spun cotton.

THE ENGLISH IN TARANTO

During the 17th century, the Venetians were replaced by the English, who came to import oil into England. Evidence of this trade is the presence of an English consul in Taranto to support commercial activities, and there was also a vice-consul from Ragusa (present-day Dubrovnik), a city that evidently equipped ships and carried out transportation for third parties.

FROM THE AUSTRIANS TO THE BOURBONS

During the Austrian period of the Habsburgs in the early eighteenth century, no attention was paid to the commercial use of ports. The lack of interest in the Apulian ports can also be attributed to the fact that they could have been potential competitors for Trieste, which in those years was taking on the role of Austria’s maritime outlet in the Mediterranean. Nevertheless, somehow the commercial traffic with northern European countries was maintained.