THE PORT UNTIL YESTERDAY

The port of Taranto has been a trading site since ancient times, a crossroads of peoples and cultures. How could it not have been when it is located in the Mediterranean, the cradle of civilisation?

From here the athletes from Taranto departed to participate in the Olympics centuries before the birth of Christ, and this was the place which the oldest guide for Mediterranean sailors calls the ‘good port’.

A ship for travelling to the Olympics

In the last decades of the 6th century BC, there is testimony to the presence of Tarantine athletes at the Olympics. Participating meant that they had to equip a ship for travelling to Greece for at least a year. And only the wealthy Tarentines who had ample financial resources, such as Anochos, could do this.

If the Tarentines were fitting-out ships, it is clear that there were shipyards, or at least someone who could repair a ship and put it in a fit state to face a long journey on the open sea.

Pan-Hellenic contests seem to have been a major attraction for the local aristocracy, which sought affirmation and approval in the noble circles of the motherland, as is also shown by the discovery of Panathenaic amphorae in local tombs, symbols of victory.

Panathenaic amphora, c. 480 BC. Found in 1959 in Taranto, via Genova, in the so-called Tomb of the Athlete. (source MArTa).

Taranto: a natural harbour since the beginning of time

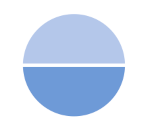

Literary sources and archaeological investigations agree in locating the basins of the ancient port along the beach of the Mar Piccolo, in the stretch from the moat, up to and including the small bay of S. Lucia, i.e. where the maritime life of the city took place until 927, the year of the destruction of Taranto by the Saracens.

The first port of Taranto

The first real port of ancient Taras must have been at the mouth of the Mar Piccolo. Useful indications to this effect can be found in the geographer Strabo (c. AD 24) and the historian Appian of Alexandria (c. AD 165

Depiction of Strabo in André Thevet, The True Portraits and Lives of Famous Men, chap. 35, page 76

a castle is born

The construction of the first nucleus of today’s Aragonese castle dates back to 780, when the Byzantines started the work of building the ‘Rocca’ [‘stronghold’] to protect the port and the city from attacks by the Saracens and the Republic of Venice.

This first fortification consisted of tall, narrow towers, from which the defenders fought with spears, arrows, stones and boiling oil.

Taranto between Late Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages, from Cazzato V., Il Porto di Taranto, Roma 1978

Medieval duties, rights and Customs

From Norman-Swabian times, the ports in the south of Italy were subject to numerous state and feudal duties paid by merchants and ship captains for importing or exporting goods, for landing (anchoring and ‘phalanxing’, i.e. the chance to plant mooring posts or make use of those already planted), for lighting in the ports (lanternage) and also for fishing.

Each province was controlled by a Royal Secreto [procurator general] or Master of Ports (in Otranto for the Territory of Otranto), under the authority of the Royal Summary Chamber, which supervised the customs officials of the province, the trades and the revenues collected by their officers called portulanoti.

The port of Taranto in the oldest portolan (pilot book)

The portolan is a practical handbook and meticulously reports all the data necessary for navigation in the sea areas to which it refers, in relation to coasts, crossings and moorings: this one, written by an anonymous person, gives us a picture of the southern ports in the Middle Ages.

The oldest known example of a pilot book for the Mediterranean Sea dates back to the 13th century. It is “Lo Compasso de navegare” (“The ship’s compass”), written by an anonymous author, possibly of Italian origin, in the medieval vernacular.

There it says:

:

“Taranto is a good port, and has II [two] islands in the sea V [five] millara [1 millara = c.1.24km] to the southeast, towards …. At the major island [San Pietro], to a good anchorage to all winds; in front of the monastery, which is in the middle of the above-mentioned main island”.

And further on we read:

: “If you want to go to the port of Taranto, put the small island [San Paolo] which is from the Greeks to the stern, and the head of the city that is from the garbino [i.e. sheltered from the winds coming from the southwest] to the bow, and thus you must enter, through a canal that is in that part of the aforementioned gulf. And respect the promontory of the city at your bows. If you can, grasp it and make fast in harbour, and at the bottom of six steps”.

Taxes, always taxes

The evidence of the oldest taxation imposed by the customs of Taranto is found in a deed of 1270, during the Angevin period.

On September 21, 1270 the then King Charles I of Anjou ordered the Procurator of Apulia (the official who was in charge of the collection of state taxes, dating back to the time of Frederick II), the Vice Procurator of the Territory of Otranto and the portolans of Taranto to allow the merchant Fusco Campanile of Ravello to set sail from the port of Taranto with his ship “S. Nicola” to export, without payment of the usual exit fee,

some quantities of flour, wheat, salted meat and various goods, evidently locally produced, destined to supply the Franco-Angevin Christian army stationed in Tunis.

Customs and warehouses

Port areas are resources, focal points, capable of attracting business and investment. In fact, a port becomes ‘attractive’ if it is able, among other things, to offer tax relief or economic incentives as well as equipment (such as warehouses to store goods or dockyards to repair vessels), promptly and safely.

These factors have affected the movement of goods at various times and brought prosperity or stagnation to the Taranto community.

The Angevin organisation of the port

The Swabians appear to have been inspired by the Arabs in creating the system of state taxation, and the origin of the word ``dogana`` `{`customs`}`, derived from the Arabic 'dîwân' (register) which in Latin becomes 'duana' and corresponds to the Greek sécreton, confirms this link.

Numerous deeds of chancery of Charles of Anjou (1226-1285) mention the fondaco [storage facilities] and the customs of Taranto, which also benefited the Church of Taranto, which had the right to tithe.

The offices of the customs house and the fondaco were located near the port, almost next to the public square, the western city gate and the bridge linking the city to the mainland, today’s Piazza Fontana.

The fondaco comprised large warehouse buildings, where goods were stored, as required by law, under the control and responsibility of the “fondachieri”. There were also guest houses, accommodation for merchants in transit.

taxes, more taxes

In the 15th century, there were various charges on shipping in the port of Taranto: the ‘jus platehaticum’ (a tax by weight for all goods bought or sold), the ‘jus fundici et exiturae’ (a tax on exports), the ‘cabella cambii’ (a tax which at that time was one gold coin for each currency conversion) and anchorage.

The port during the Spanish viceroyalty

Camillo Porzio, a Neapolitan lawyer, wrote a letter in 1575 to the Viceroy of Naples about the state of the ports of the kingdom and about the Territory of Otranto in which he says:

‘It has two ports as noble as there are in all Europe, Taranto and Brindisi. It is true that the mouth of the one in Taranto has been filled with stones and soil, so that large ships cannot enter. I am persuaded that this was done by the villagers at the time of the Saracens to deprive them of the comforts of that port.”

The appearance of the port of Taranto and the city in a drawing from 1580, held at the Angelica Library in Rome (Da Porsia F., Scionti M. , Bari 1989)

The Customs in the Habsburg period

During the years in which the Kingdom of Naples passed to the Habsburgs of Austria (1707-1734) considerable quantities of oil passed through the port of Taranto. In 1732, for example, 4,314 “salme” of oil were exported, equal to about 776 tons of product. For each salma, the port customs required 1 ducat.

In addition to oil, many other goods were transported by ships coming from the European countries most active in maritime trade, ‘England, Holland, Spain and Portugal’, reported Cassinelli, and they all fed the rulers’ customs revenues.

In the eighteenth century, black mussels, oysters, wheat, fodder, wines, wool, oil, cheese and ‘bombace’ (cotton) were exported: fleets all over the world expanded their commercial networks and volume of trade. Taranto was also part of this accelerating world.

the moat and the navigation canal

The 'moat' that we identify today as the navigation canal under the swing bridge, which allows communication by sea between the Mar Piccolo and the Mar Grande, was built during the period of Roman rule, at the beginning of the first century AD.

Both literary sources and archaeological excavations make it possible to locate the harbour basins along the beach of the Mar Piccolo, from the moat up to and including the S. Lucia inlet, i.e. where the city’s maritime life took place until 927, the year of Taranto’s destruction by the Saracens.

In 1481, under the Aragonese, a first navigation canal was built, narrower than the present one and with irregular banks, to allow the passage of small boats and improve the castle’s defendability. At that time, the ancient passage built during the Roman Empire was obstructed by debris. The management of the works was entrusted to Marco Antonio Filomarino, viceroy of the Territory of Otranto. The work was completed in 1484.

During the 16th century, under the Spanish Viceroyalty, the canal was cleared-out several times and even mussel farms were located along it. Towards the end of the 16th century, the moat was excavated further to ‘permit the galleys to enter Mare Piccolo’ .

The reopening of the moat in the 18th century

In 1755 work began to reopen the canal ditch, by order of Charles III (King of Naples 1734-1759).

The work carried out in the middle of the eighteenth century did not directly concern the port basin, which was, in any case, in fairly good condition in its outer part – the Mar Grande – but rather the artificial canal, which at that time was full of algae and debris. The intervention, ordered in 1755 by Charles III (King of Naples, 1734-1759), aimed to restore communication between the waters in the two basins, Mar Grande and Mar Piccolo, to re-establish an environment suitable for the fishing industry. In the meantime, all the main Apulian products were traded in the port of Taranto: wheat, oil and wool.

The map drawn by Henry Swinburne on the basis of the one created by Ottone de Berger in 1771 (source Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection)

Pacelli's Salento Atlas

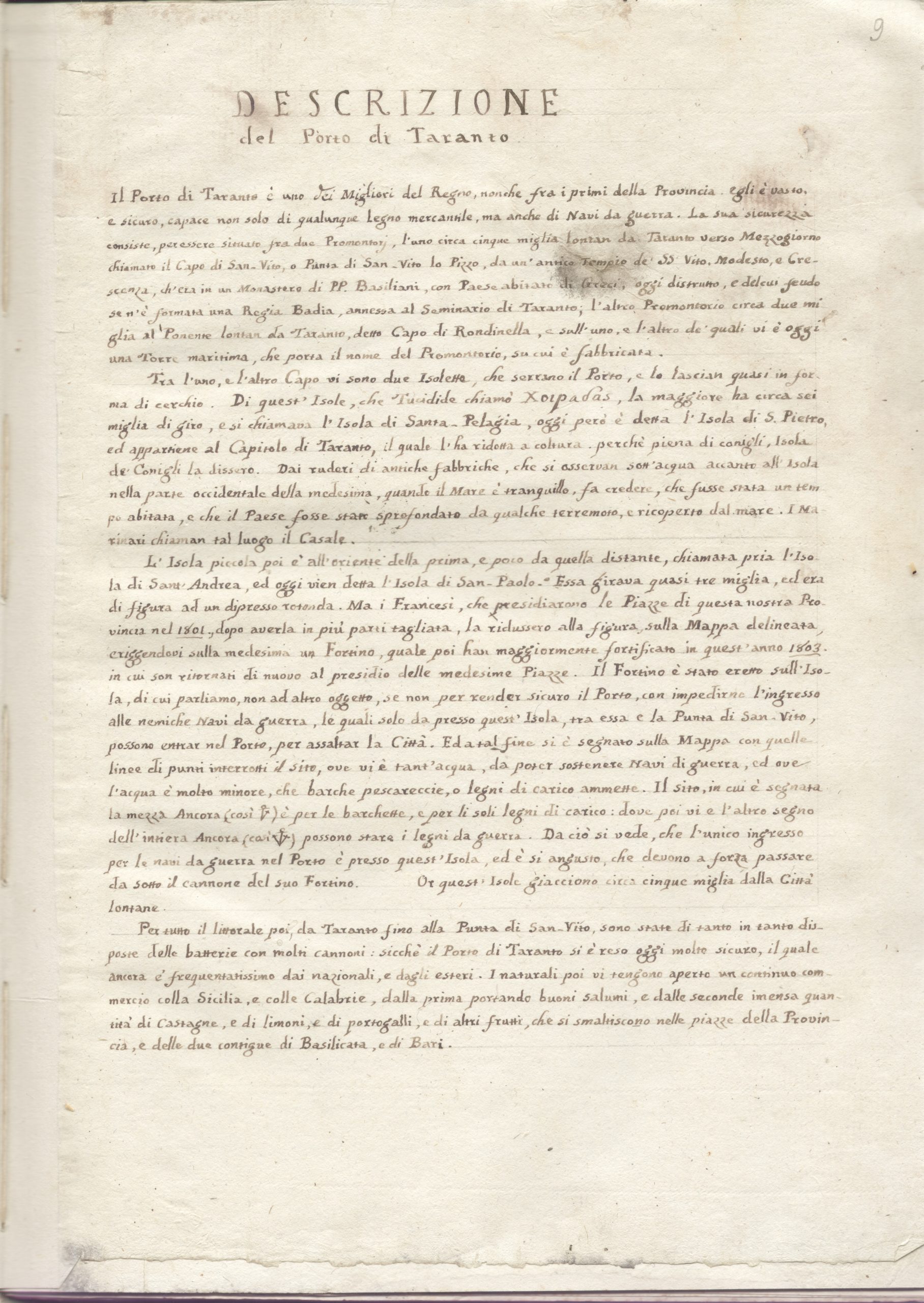

At the beginning of the 19th century, the Mandurian geographer Giuseppe Pacelli (1764-1811) sketched the whole of Salento, starting from Taranto. He describes its port as ‘one of the best in the Kingdom. It is vast and safe, in the form of a theatre, about 18 miles around, and capable of carrying any kind of wood, even for war”.

Pages from Pacelli’s Salento Atlas in which he describes the port of Taranto, drafted around 1803 (courtesy of the De Leo library in Brindisi).

Taranto at the time of Italian Unification

In 1860, when Taranto became part of the Kingdom of Italy, it had just 27,000 inhabitants. But from that year, for many southern cities, the economy reawakened: agriculture, trade, industry and navigation began again. With employment and greater prosperity, the population also grew.

If in the first decade the population did not increase, because the city was undergoing transformation, in the following years it developed tremendously; if in 1871 the population was just over 27,000, a decade later it was 34,000; in 1900 it had risen to 60,000; in 1910 to about 70,000; in 1920 to about 105,000 and in 1950 to about 170,000. This demographic development has few parallels in other Italian cities, and is one of the largest recorded in the official statistics.

Under the last of the Bourbons, the mercantile port had fallen into a real crisis; the products that flowed in from Lucania and Calabria were landed with small haulage boats in the short natural cove to the north-west, sheltered but without quays or port facilities. After 1860, the idea was to enlarge the port and make it suitable for the large steamships that modern technology had created, and various projects were drawn up.

In 1886, with government funding a 100-metre dock was built at what is now St Eligius’ Quay. In the same year the navigation channel was dredged to improve the passage between Mar Grande and Mar Piccolo.

In 1887, near the Porta Napoli bridge, the quay known as the ‘Dogana Regia’ (Royal Customs House) was constructed, with just enough excavation to allow small capacity sailing ships to dock. During this period, discussions were held on whether to build the mercantile port in Mar Piccolo or in Mar Grande, where it is today.

1908 Porta Napoli bridge (Rassegna pugliese 1913)

1900 ca. Mercantile Port (Rassegna pugliese 1913)